Being, Seeing, Wandering. These three words resonate through over 120 photographs displayed in a partitioned section of the Berlinische Galerie, also known as the Museum of Modern Art in Berlin. This is the title for the exhibition of the photographic works of the Berlin-based Nigerian-British photographer Akinbode Akinbiyi. For over 50 years, Akinbiyi has crisscrossed cities, countries, and continents with a camera, photographing almost daily. Having lived in Berlin since 1991 and photographed the city extensively, Akinbode Akinbiyi was awarded the State of Berlin’s most important art award, The Hannah Höch Prize, in 2024. This award honors artists who have made significant and innovative contributions to contemporary art.

The Berlinische Galerie was the chosen museum for the retrospective exhibition that accompanied the award. It would be Akinbiyi’s first-ever solo exhibition hosted by a German museum. It also necessitated the first comprehensive book publication of his work.

Born in Oxford, England, in 1946 to Nigerian parents, Akinbode began photographing seriously sometime in 1974 after studying English and Literature in Ibadan (Nigeria) and Heidelberg (Germany). Photography would eventually become the means to merge his youthful aspiration to become a writer with the irresistible pull of the camera.

Speaking of the camera, Akinbiyi has worked with one type for almost all of his career – the Rolleiflex twin-lens reflex camera. The first time I met Akinbode Akinbiyi was in 2002, in Lagos. He had returned from Berlin and visited the studio where I was then an apprentice to the photographer, Uche James Iroha. Back then, he carried the made-in-Germany Billingham bag with which he carries his camera even to this day.

Much of Akinbiyi’s photographic fluency can be traced back to his mastery of the camera. Elsewhere, he has likened this to the relationship a musician has with their instrument. In a 2020 conversation with the curator Natasha Ginwala, the word evoked was Riyaz, referencing a practice in the Hindustani classical music tradition, which entails a rigorous exercise to master certain vocal or dance forms. This patient, seemingly effortless yet cumulative dedication to the act of seeing through the instrument, over five decades, has led to an accordion of meticulously composed photographs with multifarious chords that reverberate like tone poems.

The works on display delve into an archive that the photographer has diligently maintained in the form of medium-format black-and-white film negatives (most of which he develops in his home darkroom) and contact sheets. I remember visiting his Berlin home in 2020, during which he showed me where his negatives and contact sheets were stored in drawers. They were carefully filed and dated from 1974 to 2019. To me, it was a jolt of realization: if you have ever walked with Akinbiyi on the street while he photographed, you would think it is one of the most arbitrary acts ever. There is no indication whatsoever of when or why he stops to photograph a scene. It could happen at any time or light of day. His mode of moving in space disrupts the chronology and linearity we have all become used to. Thus, to make sense of his way of being in space is to relegate it to some randomness. Yet, this couldn’t be further from the truth. Now, at the exhibition, the audience is presented with the coherence of 50 years of being, seeing, wandering, and dancing in the transitory space of what John Berger describes as “between appearance and revelation.”1

Structured thematically into six bodies of works realized between the 1980s and the present day, Akinbiyi’s photographs are, on a broader scale, a subjective rendition of the sociopolitical unfolding of their time. For over five decades, Akinbiyi has traveled far and wide and photographed extensively. But his trajectory has oscillated triangularly, mainly around Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The works exhibited in Being, Seeing, Wandering come from the photographer’s walks in public spaces, often in transit to scheduled events such as masterclasses, exhibition installations/openings, or simply personal visits. It has always fascinated me that his photographic preoccupation, all these years, has been an offshoot of some other center-stage engagement he was invited to. Yet this has allowed Akinbiyi to be one of the most accessible, mobile, and present artists while reserving a reclusive space for his photographic work to flourish. Although you will always see him clutching his camera bag, you never get the impression that his camera comes in the way of anything. There is always a wholesome balance between relaxedness and attentiveness to the moment. This, too, is evident in the photographs.

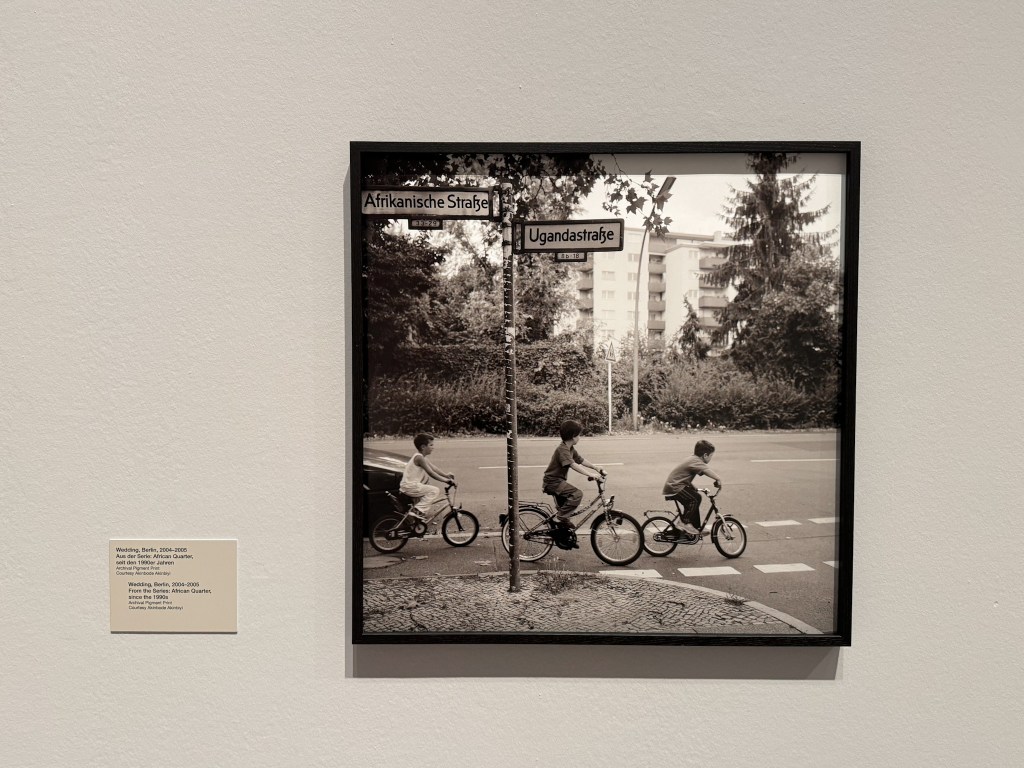

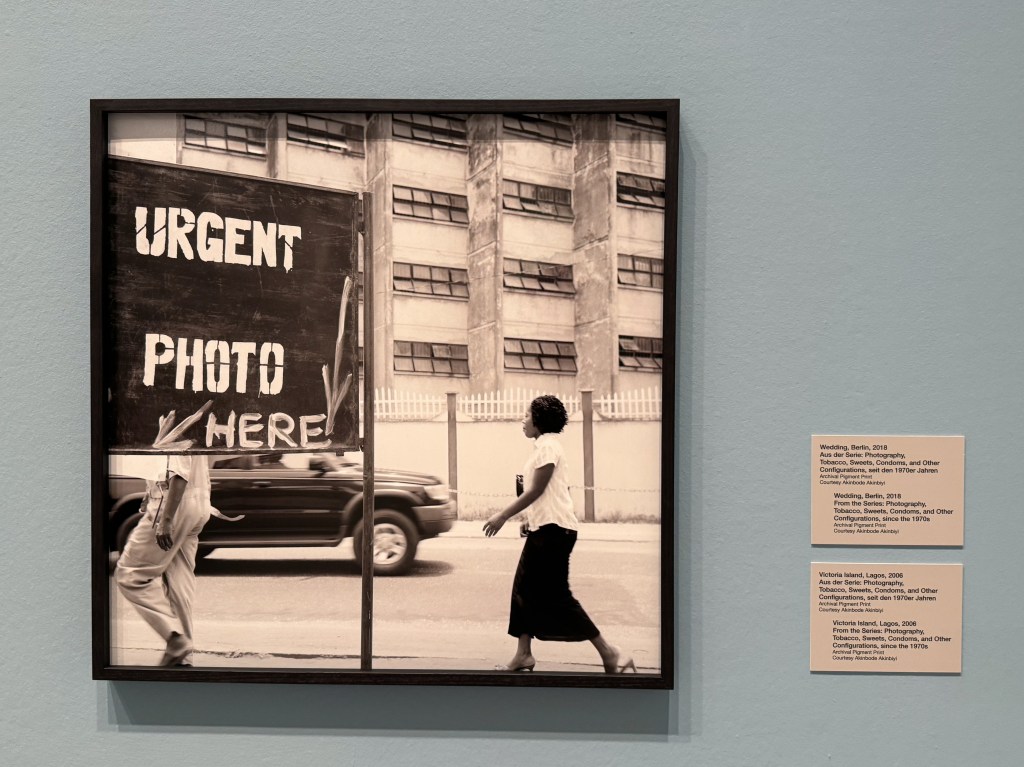

Considering his peripatetic approach to witnessing moments unfold and coagulate into history through his lens, the photographs come together as footprints of an attempt to remap – through presencing – the cartography of a shared world, as if to suggest what the French-Martiniquan thinker Edouard Glissant calls a world in relation. Indeed, by virtue of Akinbode’s movement, places, things, people, circumstances, and events are correlated, making the photographs sites of encounters. Although underscoring all of his works, this is most apparent in the series “Photography, Tobacco, Sweets, Condoms, and Other Configurations” (1970s – present), which draws the audience’s attention to how public spaces are sites of political interventions and social dramas, whether in Lagos, Berlin, Durban, or Brasilia. His photographs of the African Quarter of the district of Wedding in Berlin (since the 1990s) are conspicuous reminders of how colonialism and racism were (and in some ways continue to be) part of everyday life in Germany,2 while those of eThekwini (1993), the township of Durban, give glimpses and vestiges of Apartheid South Africa.

The prints, mounted in glass and mostly framed in black wood, vary in size. Spatially, the photographs seem guided by numerical considerations. The numbers 6, 3, and sometimes 2 appear as recurring guidelines or patterns. In the esoteric world of numerology, these numbers are associated with balance, harmony, and coherence. The coincidence of these numbers with the spatial design of the exhibition is not lost on the photographer. This is evident in the series See Never Dry (since the 1990s), where Akinbiyi’s photographs of Lagos Bar Beach numerically correlate people, animals, objects, and the shoreline. He views these numerical references as pointers to significant synchronicities, especially when recurrent in a scene or over time. He is also aware of the importance of numbers in the Yoruba cosmology.3

Akinbiyi is usually thought of as a “black-and-white photographer” since most of his works are monochromatic. However, in this exhibition, we see, perhaps for the first time, 15 color photographs from the photographer, comprising the series African Spirituality (2002), arranged linearly across the wall of the largest partition of the space, as if to serve as a useful spin without obstructing the flow of the rest of the images.

“Photography is a powerful conundrum. What is it?”

Akinbiyi’s photographs are neither accidental nor foreshadowed by stylistic intent. Rather, they stem from a deeply held urge to understand the nature of things – to accord a place, a thing, a person, or a feeling the benefit of understanding. It is to say, things are what they are for a reason. But what is it? And what is the reason? The Igbos (of Eastern Nigeria) say: Onye ajuju anaghi efu uzo, which loosely translates as one who questions never goes astray. In Akinbiyi’s photographs, the questioning is not reducible to a quest for an answer. Instead, it is an orientation mechanism in countless strands of roads and bypaths. The word “conundrum,” in this case, is not a deterrent but rather a call to look, look away, and then look again.

Akinbiyi identifies as a wanderer, often clarifying that this should not be conflated with Baudelaire’s flâneur,4 as critics of his work sometimes do. The difference here is subjective in the sense that, to Akinbiyi, the wanderer is not confined to the concept of “aimless strolling” but is imbued with a sense of a sprawling world and countless in-betweens. In the short film I Wander as I Wander: On Akinbode Akinbiyi (2020), he speaks about the journey as self-referential, where he is constantly going back and forth between the past (childhood), the present, and what comes next, trying to understand the ebb and flow of life along the way. This self-referential attribute of the wanderer lends his photographs their aura of quiet sensitivity.

This quiet sensitivity – like a thin, effusive layer – is almost smothered by the heavy-handed attempt to frame the exhibition within its sociopolitical discourse, if one allows themselves to be overly guided by the wall text. Understandably, it is the nature of museums to attempt a grandiose historicization of major exhibitions. In this case, however, it risked pigeonholing (albeit unsuccessfully, to the discerning eye) the poetic reach and generosity of the work.

The postcolonial underpinnings of Akinbiyi’s work are implied within a more expansive reading that – much like the works of contemporaries such as Stuart Hall, Santu Mofokeng, David Goldblatt, and John Akomfrah – seeks to synthesize the moving parts resulting from post-independence Africa and weave them into coherent intersections of the “here and elsewhere,” then empty them into the present time to point the way to more sensitive paths for the younger generation to tread.5 Thus, it is no surprise that, beyond his photographic work, Akinbiyi has dedicated so much of his practice to mentoring younger generations of thinkers, photographers, and artists without geographical preference.

In Being, Seeing, Wandering, Akinbode Akinbiyi’s photographs draw the viewer inwards; beyond the subject matter, into themselves. They encourage an encounter with the self, which is no more than a way of being, seeing – sensitively. They urge us to become wanderers of our inward journey, a self-referential journey. This is what makes the exhibition so relevant in a time marked by a loss, both of moral compass and of sensitivity to the plight of the other.

Emeka Okereke

Berlin, 2024.

1 John Berger (1926–2017) was an influential English art critic, novelist, and author of Ways of Seeing (1972). He explored how art and photography reveal deeper truths beyond surface appearances, emphasizing the interpretive space between what we see and what we understand

2 Germany’s African Quarter (Afrikanisches Viertel) in Berlin reflects the country’s colonial past, with many streets originally named after colonial figures and events linked to its brief but violent imperial period in Africa, particularly in Namibia. Streets like Lüderitzstraße and Petersallee were named after figures like Adolf Lüderitz, a German colonialist in Namibia, and Carl Peters, a colonial governor. These names have been the focus of activism, and although some names have been changed, such as Lüderitzstraße being renamed Cornelius-Fredericks-Straße in 2022, a few names remain contested to this day. The renaming process has been ongoing, with resistance from some residents and political figures.

3 In Yoruba cosmology, numbers hold profound symbolic significance, reflecting the intricate order of the universe. Each number is associated with specific deities, spiritual principles, and cosmic forces. For instance, the number 1 represents the supreme deity Olodumare and unity, while 3 symbolizes the tripartite nature of existence (heaven, earth, and the underworld). Numbers also play a crucial role in rituals, divination systems such as Ifá, and the structuring of traditional ceremonies, reinforcing the belief that numerical patterns embody divine truths and influence the natural and spiritual realms. Akinbode Akinbiyi’s Nigerian lineage is Yoruba.

4 The flâneur is a concept in 19th-century French literature, representing a leisurely urban wanderer who observes modern city life. Akinbiyi’s wandering, in contrast, suggests a more deliberate and continous engagement with the world deeply rooted in a personal, self-reflective process of orientation.

5 Postcolonialism is the critical examination of the cultural, political, and social impacts of colonialism, focusing on regions formerly under colonial rule such as Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and Latin America. In the latter half of the 20th century, artists and intellectuals from these regions played a pivotal role in advocating for a nuanced and hybridized understanding of global geopolitics as a way of transcending the limitations and confining effects of colonial borders and mindsets.